HTTP 101

...what one should know about HTTP...

After explaining the basics of HTTP to a number of people around me, I decided I should write it up.

Introduction:

HTTP means HyperText Transfer Protocol. A protocol is just a convention for computer dialogs. The same way that you don't start a conversation with somebody by saying "goodbye", or that you don't interrupt somebody speaking, computers need to follow certain "social" rules when communicating.

It assumes that the computers participating in the conversation have a way of sending messages to each other.

This is implemented by other protocols that go into the details of how electronic signals should be sent on the wires. These implement an abstraction, called sockets, that looks pretty similar to a tube that transports letters.

When two computers have set up a socket between them, they can start sending words to one another, it is just a matter of sending words in a way that they both can make sense out of them and don't stay silent when it's their turn to "speak".

Request & Response:

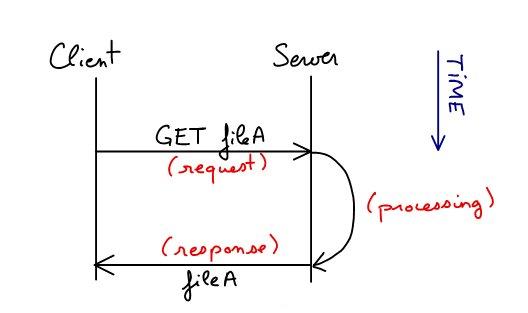

HTTP uses a simple conversation pattern: the client connects to the server with a socket, initiates the dialog by asking the server for something, the server then tries provide the client an answer back.

An analog of a simple HTTP request and response would be the client asking "give me the file A" and the server answering "I have it, here is the content of file A: (...content of file A...)".

But in reality the protocol uses its own simplified language which looks more like "GET /fileA" answered by "200 OK (...content of file A...)". Check the links at the end of this article for the complete reference documents.

We'll now go into more details of what this language looks like.

Loading a web page:

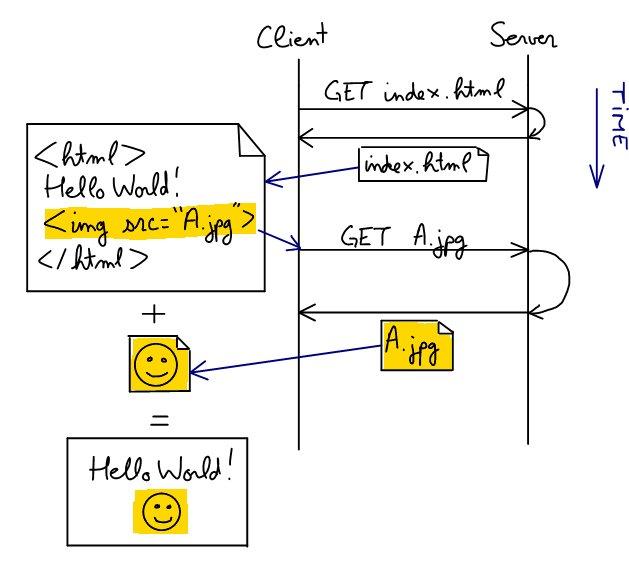

When a browser loads a web page, it does a GET request for the url requested. The content of the page is usually in a special text format called html, that allows to include links, images and other style effects.

The browser analyses the html in order to display it to the user. But doing so it may find that it needs more content to render the page correctly, like images.

When that happens, the browser initiates one HTTP request for each image.

When all the necessary information is downloaded, it is combined into the page the user sees on his screen.

Experiment:

Telnet is a program that lets you establish a socket connection to a server and manually type the characters you want to send. The command-line syntax varies a little bit, but the principle stays the same: you want to provide the name of the server and a port number. The standard port number for HTTP is 80.

Try the following:

In a windows command prompt, type "telnet google.com 80" followed by return.

A connection will get opened and you are now free to send characters to the google server.

You can quit the telnet program at anytime, by hit (control) ] then type "quit" followed by return.

Continue typing: "GET / HTTP/1.0", followed by return twice.

Depending on the telnet program, the characters you type might appear in the console, or not (but you can type it blindly).

This is the simplest request you can send.

The extra blank line signifies the end of the request and as soon as you type it, the google server will start replying something like:

Content-length: 3266

Date: Fri, 26 Mar 2004 22:13:00 GMT

Content-Type: text/html

Cache-control: private

Set-Cookie: ID=09ac55c2fbb3def1; expires=Sun, 17-Jan-2038 19:14:07 GMT; path=/; domain=.google.com

Server: GWS/2.1

<html>(... google's html page ...)

Request & Response format:

Both the request and response have three parts: the first line, which is either the request line or the status line, a number of introductory lines, called headers, and a content block, called the body.

The request line says what resource the client is trying to access and the status line provides the status of the processing for the request.

Request format:

(...headers...)»

»

(...body...)

In our simple experiment, we didn't have any headers in the request, we just had the GET line followed by a blank line.

The action in this case is a GET which is the most frequent one and is used for getting files. But other actions are available, like POST, used when the browser wants to send the content of a form back to the server. Both are very similar except for the fact that POSTs use the body of the request (to send the form data) whereas GETs don't have a body.

Note that line breaks are represented by a pair of special characters, a carriage return followed by a line feed.

The server can choose than handle requests like GETs by either returning static or dynamic content. For example, when you get a file, the web server just loads the (static) file from the hard drive and sends a copy back to you. But it is also possible that the content be built on the fly (dynamically), like Google's search result.

In most case where the result is generated, more parameters can be passed to the server using a special format called querystring. Instead of just asking for a given path like /fileA, you would ask for /serviceA?param1=value1¶m2=value2.

For example, if you perform a search on Google, you'll notice that the words you typed in will appear in the url of the results, as a parameter called "q".

Response format:

(...headers...)»

»

(body: content of file A)

The request format makes it easy to tell when the request is over. In the case of a GET, when a blank line is received, the server can starts sending the response back.

First it sends the status code (200 means the file was found) with a short description text, followed by some headers (to specify things like the size of the file or the last time it was updated) and terminated by an empty line. Then it sends the content of the file.

The client knows he has received the whole file either by checking the length of what he has received against what was announced, or if the length wasn't specified, by waiting for the server to close the connection.

More status codes are available, like 404 (File not found), 302 (Resource has moved) or 500 (Internal server error).

POST action:

When you fill a form in a web page and click the submit button, the browser generally do a POST request back to the server. Let's consider a registration form that prompts you for a user name and password, then the request might look like:

Content-Length=30»

»

username=dumky&password=secret

When the server receives a POST for the form submission url, he'll look at the body of the request (username=dumky&password=secret) which uses a standard format, and extract the username (dumky) and the password (secret).

Then he'll check whether the username is already taken. If so, an error page is returned. Otherwise, the new username and password are stored in the server's records and the registration succeeded.

Headers:

Headers allow for extra data to be passed with the request and the response. Each line looks like Header-Name: header;data.

One of the most frequent headers that can be found in an HTTP response is the Content-Type. It tells what kind of content is being returned. Each media type has a special name (mime-type): a text file would use text/plain, an html file text/html and a jpeg image image/jpeg.

Another one is the Content-Length. It tells the client the size of the content being returned.

For 302 and other 3xx redirection status codes, the response should also contain a Location field that points the browser to the new location for the resource.

The request can also contain headers. For example, the Accept header field allows the client to restrict what media types the server should send back.

The Referer field indicates the url where this link was found. For example, if you are on a google page and click on a search result at yahoo.com, your browser will tell the yahoo.com server that it came via that google page.

Some header fields are a bit more rich, like Set-Cookie and Cookie (described in HTTP State Management Mechanism), as they work as a team.

Whenever a response contains a Set-Cookie directive, with a certain cookie value, the browser is supposed to send that value back to the server in subsequent requests, using the Cookie field.

This is a way for the server to avoid remembering some things, but asking the browser to remember them instead.

Other headers are available to make HTTP more efficient, like cache directives. Also there is a way to chain multiple requests and responses re-using the same connection (Keep-Alive field in HTTP/1.1), because opening new connections takes time.

Conclusion:

HTTP is rather simple once you understand the fundamentals. It's just a question of learning new actions and headers.

It is a rich and extensible standard, defined across many reference documents, so it feels like you can always find some new hidden features.

But it is most definitely a worthwhile topic to learn, even if you don't work in web development, as HTTP really is universal.

Let me know if some parts of this article need some further clarifications.

Links:

The specifications of HTTP version 1.0 and HTTP version 1.1.

This is very good, I do not see any errors on a first pass. There have been other writeups and books about the subect of course, but this is an accessible description of the protocal. There are a couple folks in my office who I should share this with. Hopefully this document will be available to the internet for years to come. Cheers!

Posted by: Shawn Medero (March 30, 2004 10:19 AM) ______________________________________Good

Posted by: rajesh (April 13, 2004 09:02 PM) ______________________________________Well drafted in simple language for a novice!

Very good, thanks

Posted by: Donal Ward (February 17, 2005 04:37 AM) ______________________________________Good and clear simple explanation even for me, whose doing web sites since 8 years (but at a content level with users) and wasn't really sure of the underlying things.

Posted by: Mario (October 13, 2005 12:26 AM)